Martha Kicsiny

Interview with the British-Hungarian artist based in Ghent, Belgium. Her artworks fuse predigital and digital techniques to understand the deep cultural traits from which our modern technology stems.

Martha Kicsiny is a British-Hungarian visual artist based in Ghent, Belgium. She is a multimedia art fellow at the Doctorate School of the Moholy-Nagy Arts University (MOME, Budapest, Hungary). Her research aims to unearth and incorporate 19th-century Media Archaeology findings into Contemporary Art and, especially Immersive Media discourses. Her artworks fuse predigital and digital techniques to understand the deep cultural traits from which our modern technology stems. Ranging from video art, site-specific installations to 3D-printed lithophanes, her practice focuses on the human condition in society, the aftermaths of historical events, the expression of power in architecture and the mythological origins of oppression and segregation.

Website: https://www.marthakicsiny.hu/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/marthakicsiny/

What guides your artistic research?

I feel a deep fascination towards the past, but also a desire to express the tension and contradictions I feel about being alive now. These might seem to be polar opposites, but I believe that connecting elements of the past and the present offers us a broader perspective. Helen Kaplinsky described the medieval experience of life as a duality between the material world and an otherworldly religious realm. Today, the virtual and digital create a similar parallel layer of existence, guiding our physical lives by something metaphysical and invisible. However, in contrast to the way we imagine the internet, this intangible realm is created by very material technology, created and run by resources that way heavy on the environment and exploited groups. This drives me to reflect on the nature of mediation, its history, politics and social impact.

What are you working on right now?

Many questions about the origins and possible alternative futures of our contemporary technology can’t be answered based on canonised art history and media history. This is why I love researching forgotten 19th-century media. I believe the essence of digital imagery is that it is made by light, so I strived to find a way to keep its light-based essence, while materialising and deconstructing the high-tech nature of screen technology. So, I revisited the historic medium of lithophanes with 3D printing. Lithophanes were porcelain screens that would glow in front of candles or gas lamps in the dark of homes at night, like how our digital screens glow today. Without the use of pigments, images appeared on the surface of porcelain when backlit, due to its varying thickness, creating an entrancing, glowing image which is slightly spatial. In the coming months, I want to experiment with further deconstructing my 3D-printed lithophanes. On one hand, I’m planning to work on incorporating some kinetic components and motion sensors to make more dynamic pieces. But I would also like to reflect on the difference between natural and electric lights. I’ve recently been given the green light to exhibit some candlelit lithophanes, which will add a whole new aspect to the images, so I’m excited to be able to experiment with that as well.

What are your favourite items in your studio? Why?

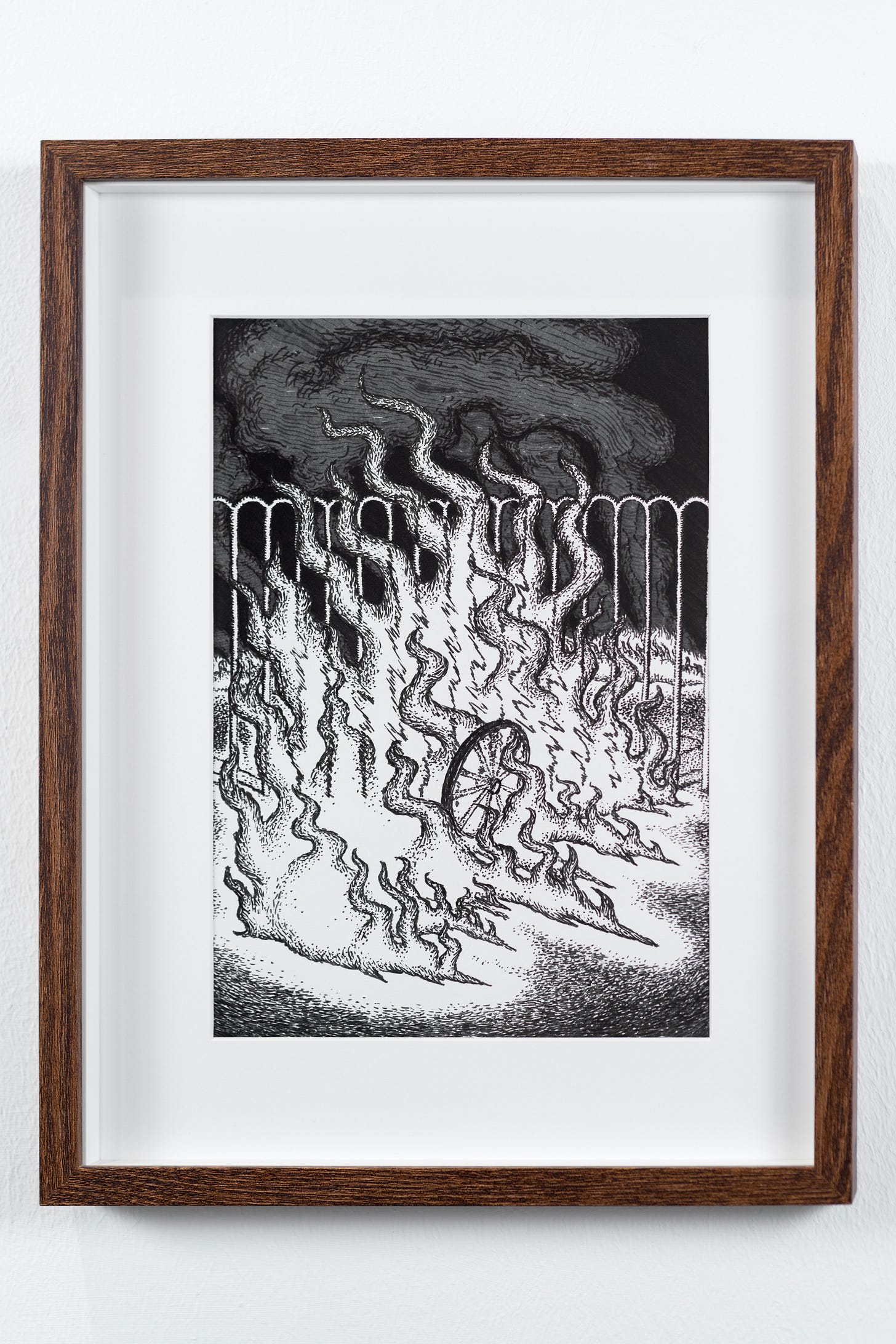

Recently, I found an amazing 19th-century freestanding carved wood fire screen frame in an antique shop in Ghent, where I’m based now. I knew it would be a real artistic challenge to make a lithophane that suits this elaborate frame, and I wasn’t even sure it would fit in our narrow staircase and small studio, but I couldn’t leave it there. Thankfully, we managed to get it in, and now I love looking at it every day. The fact that it is a fire screen perfectly fits my research on lithophanes, and I love working with the symbol of fire. I can’t wait to incorporate it into a project soon!

What are you curious about? What would you like to explore further?

Technofeudalism is a topic that I find very relevant, as the global platforms of the internet create a new layer of reality, thus causing tensions and schisms. While the internet seemingly offers such freedom and possibility for individuals, it also creates a fragmented vulnerability exposed to forms of exploitation previously unknown. As some, such as Yanis Varoufakis, have pointed out, the evolving cloud power structures echo those of the feudal Middle Ages. Living in Ghent, a city where the medieval past is very much present, I often feel strong resonance between the Middle Ages and the present. I would love to research this topic further and focus on historic tactics of resistance and resilience against feudalism that we could learn from today, such as the Ghent revolts against the Holy Roman Empire.

What was the last thing that made you laugh out loud?

I really enjoyed watching The Studio; it’s a self-reflective satire, a not-too-serious comedy series made about the creative industry. It’s a great way to have a good laugh about the absurdity and complexity of trying to survive making art while navigating financial realities and social pressure. The dynamic cinematography, punchy script and intense music score have a catchy momentum, so it also gives energy to just get on with it.