Annie Edwards

Interview with the artist, lecturer, and international residency curator based in London, UK. Her multidisciplinary practice investigates embodiment, material agency, and feminist critique.

Annie Edwards’ essential area of focus is the human body. Her multidisciplinary practice distorts our familiar sense of reality by incorporating robotic, figurative sculptures with abstracted skeletal forms. Annie’s installation and performances aim to understand the body from biological, psychoanalytical and social perspectives. Her research choreographs the tension between body and machine, embedding visceral knowledge into mechanical gesture. Annie references wider systems of control present in domestic, medical and industrial environments, drawing on her personal experience of trauma, neurodiversity, atopic illness, and her background in farming.

Website: www.annieedwards.com

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/a_knee___

Annie Edwards was recommended by Aura Sun.

How would you describe your work?

My practice centres on the human body as a site of tension, mediation, and meaning. Working across sculpture, installation, and performance, I disrupt familiar bodily realities through the combination of robotic, figurative forms and abstracted skeletal structures. I use these hybrid bodies to investigate embodiment through biological, psychoanalytic, and social lenses. My research stages an ongoing negotiation between flesh and machine, translating visceral, lived knowledge into mechanical movement and gesture. Referencing systems of control embedded within domestic, medical, and industrial contexts, my work is informed by personal experiences of trauma, neurodiversity, atopic illness, and my upbringing within agricultural environments.

What themes and motifs do you explore in your art?

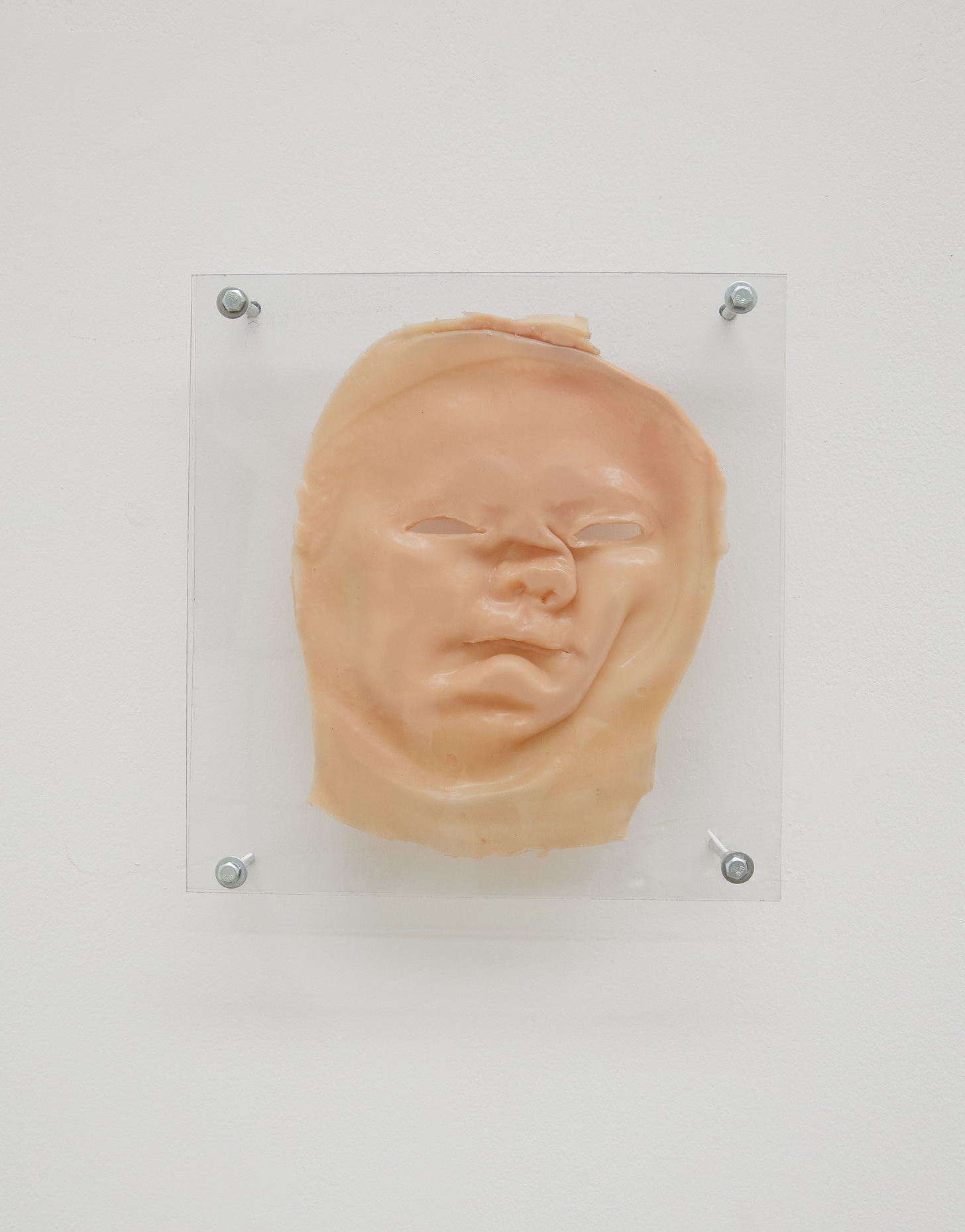

My work interrogates the boundaries of skin—its texture, tone, and tension—both as a surface and a symbol. Skin becomes the barrier between what is hidden and what is exposed, a juxtaposing membrane of encasement and vulnerability. Through processes of building, dissembling, and rebuilding, my fragmented forms evoke the containment and expression of trauma within the body and brain. Drawing from abattoir architecture and my rural upbringing, I create visceral metaphors of consumption, where bodies are reduced to objects within a system. I use humour as both a disarming and subversive tool, addressing the parts of the body we are conditioned to shy away from. My work embraces the grotesque and the abject as strategies to confront both the beauty and discomfort of embodiment—using the language of the body to expose what is usually hidden, repressed, or deemed unacceptable. Ultimately, my work asks the viewer to reckon with their own embodiment, their own complicity, and their own capacity for tenderness.

What drives you to do what you do?

My work is driven by a desire to expose how bodies and minds are disciplined, misread, and controlled when they fall outside ideals of productivity, coherence, and femininity. My practice is grounded in lived experience and feminist thinking, and emerges from navigating trauma, neurodiversity, and gendered medical bias within systems that privilege linear functioning and compliance.

I am driven by a desire to challenge the myth of the “functional” body and mind. Experiences of PTSD and dyspraxia have made me acutely aware of how dysfunction is framed as personal failure rather than as a response to social, medical, and industrial pressures. Using my own body as a site of resistance, I work with fragmentation, repetition, absurdity, and humour to undermine expectations of control, efficiency, and aesthetic coherence. Humour, in particular, allows me to subvert authority and to challenge misogynistic assumptions about women’s bodies, labour, and intellectual capacity—including the persistent notion that women are not funny or capable of sharp, disruptive wit.

My performative work is driven by an impulse to expose what is usually hidden: disrupted gestures, repeated attempts, laboured rhythms, and moments of failure that mirror forms of executive dysfunction often masked from view. By drawing parallels between domestic labour, medicalised femininity, and industrial systems of production, I reposition dysfunction not as deficit, but as critique. Failure becomes a strategy of refusal—an embodied protest against hyper-efficiency, self-surveillance, and compliance.

Ultimately, I am driven by a need to confront how women’s bodies are observed, assessed, and objectified. I am interested in the power dynamics of the gaze—how judgement is imposed, internalised, and performed. By implicating the viewer within these dynamics, my work asks them to reckon with their own role in systems of control, care, and harm. Through this, I seek to reframe vulnerability, failure, and messiness as sites of agency, resistance, and collective recognition.

When you feel stuck, how do you get un-stuck?

My studio is full of playful, absurd and joyously grotesque objects and sculptures. It’s a great place to be if you feel stuck. There are endless combinations of items to interact with that have the power to heave anyone out of a rut. I am a lecturer and made an extensive list of prompts routed in play for my students to turn to when they experience creative block. I call it the Blocksmith list. Prompts might include taping a pencil to something heavy and drawing with it, or creating an installation using only toilet roll and light. These exercises interrupt habit, reduce pressure, and allow thinking to happen through action.

What kind of atmosphere do you like when you work?

I am a huge advocate of artist residencies and I find this to also be one of the most impactful ways to reinvigorate and nurture new ideas. Residencies radically shift pace, context, and expectation, creating space for risk, failure, and recalibration. My time at Joya:AiR Arte + Ecología, Spain in 2024 and Argo Arts, Athens in 2025 were particularly formative, and out of those experiences I developed a residency programme linking both places to the Royal College of Art. The programme creates a pathway between institutional study and independent, site-responsive practice, offering early career artists time, distance, and support to experiment without the pressure to immediately resolve or professionalise their work.

Being embedded in these environments—through shared labour, conversations, isolation, and immersion in place—allows ideas to unfold slowly and unpredictably. Ultimately, getting unstuck for me is about introducing play, displacement, and generosity: towards materials, towards process, and towards myself.

Who do you recommend for the readers to check out?

I’d encourage readers to look at the work of Rosie Gibbens, whose curatorial approach to the absurd, the grotesque, and humour has been a major influence on my thinking—particularly during my degree show.

Another creative force I’m deeply excited about is OHSH Projects. They’re a nomadic project space in London founded by Henry Hussey and Sophia Olver with a real commitment to creating tactile, textural conversations between artists and spaces. Their playful and contemporary themes often draw on mythology, memory, identity, the raw human body and symbolic storytelling. They create exhibitions that feel urgent, immersive, and resonant by utlising spaces like former restaurants, station waiting rooms and raw industrial environments, giving artists the freedom to experiment outside the usual commercial or institutional frameworks. I love how their programming is bold and funny, intellectually stimulating but never aloof, and fiercely supportive of both emerging and established practices. I have the honour of showing with them in early January.

What inspired you recently?

Most recently, Athens has been a huge source of inspiration for me. The creative communities in Exarchia and Kypseli are so vibrant, generous, and full of mutual support. It felt like everywhere I went there was something to spark my imagination—private views almost every night, conversations in the streets, and a palpable sense that art is lived communally rather than isolated in white cubes.

What are you curious about? What would you like to explore further?

What I’m curious to explore further is how art can sustain and radiate that same sense of communal generosity—how we can make spaces and practices that don’t just show work but nurture it, invite people in, and make experimentation feel like a shared, joyful risk rather than something solitary or pressured.

What makes an artwork “good” in your opinion? Why?

This is a question I return to every year with my students, and one I don’t think has a single answer. There are many valid ways to define a “good” artwork—evidence of time and care, technical skill, scale, surprise, mystery, or a sense of awe. These qualities often signal commitment, intention, and attention, and they matter.

For me, though, what makes an artwork compelling is complexity. I’m drawn to work that holds more than one emotional or intellectual position at the same time. This is why I’m so interested in the grotesque: it has the capacity to pull you in through intrigue while simultaneously pushing you away through discomfort or revulsion. Comedy and darkness often operate in a similar way—shock and laughter arriving together, destabilising certainty and making space for deeper engagement.

I also believe strongly in the importance of multi-sensory experience. We move through the world with our whole bodies, not just our eyes, and I think art should reflect that. Work that considers sound, texture, scale, movement, or atmosphere creates an embodied encounter rather than a purely visual one. For me, a “good” artwork doesn’t just ask to be looked at—it asks to be felt, negotiated, and physically experienced.